|

Brussels, |

|

Gas - Shale Gas & others

About one quarter of all the energy used in the EU is natural gas, and many EU countries import nearly all their supplies. Some of the Member States are also heavily reliant on a single source or a single transport route for the majority of their gas. Disruptions along this route caused by infrastructure failure or political disputes can endanger supplies. EU.

The EU, with the European Geen Deal, has set itself the objectives of decarbonisation by 2030 and neutrality by 2050. Fossil gas constitutes approximately 95% of the gaseous fuels consumed in the EU in 2021. Gaseous fuels represent around 22% of total EU energy consumption today (including around 22% of EU electricity generation and 39% of heat generation). For this reason, the EU has targeted fossil gases and intends to drastically and rapidly reduce its consumption and to create the EU hydrogen market.

In this contest, on 15 December 2021, the Commission adopted a Proposal for Directive on common rules for the internal markets in renewable and natural gases and in hydrogen (see below the presentation).

For more specific EU initiatives on hydrogen, go to the Hydrogen page.

Consumption and demand

About 26% of natural gas is used in Europe in the power generation sector (including in combined heat and power plants) and around 23% in industry. Most of the rest is used in the residential and services sectors, mainly for heat in buildings, i.e. more than 40%.

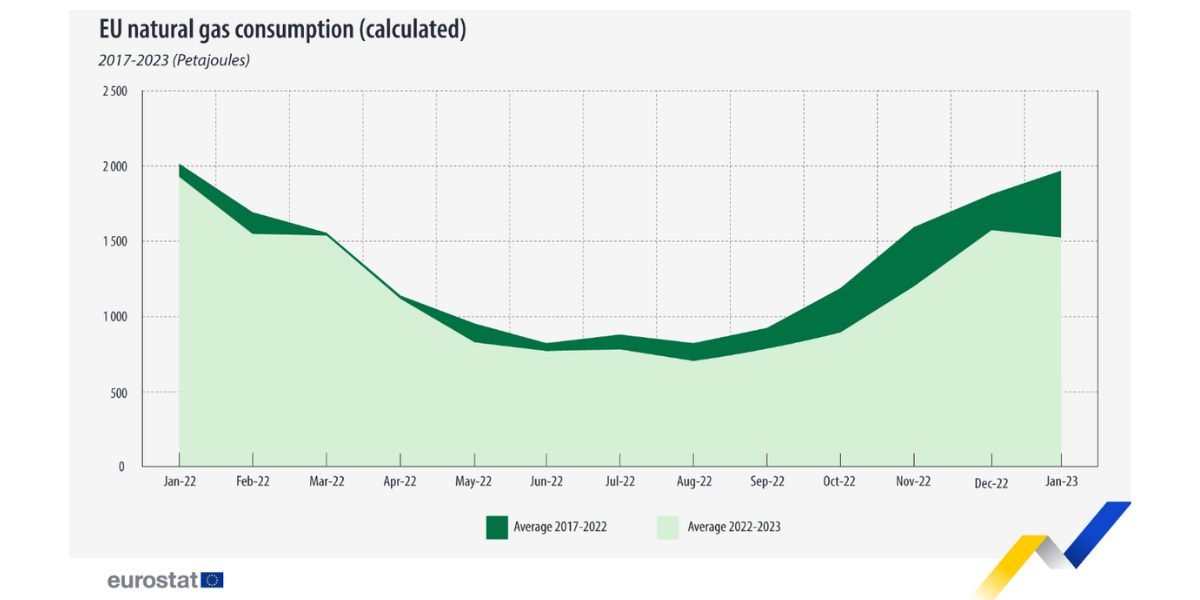

Between 2022 and January 2023, consumption in the EU was lower than in the period 2017-2022. Between January and July 2022, EU natural gas consumption varied between 1 938 petajoules (PJ) in January and 785 PJ in July, indicating an overall monthly decrease, even before the 15% gas reduction target was set by Council Regulation (EU) 2022/1369. But the greatest drops were recorded in the second half of the year starting from August 2022, with a reduction in consumption of 14.0%, followed by 14.3% in September, 24.7% in October and 25, 0% in November.

Consumption in December 2022 touched 1 575 PJ, indicating a smaller decline (-12.6%) than in previous months, but then decreased further in January 2023 (-22.1%).

January is seasonally a colder month with higher consumption, yet, in January 2023 (1 534 PJ), the reduction in consumption was evident compared to December 2022 (1 575 PJ) and January 2022 (1 938 PJ).

Liquefied natural gas

The EU is the biggest importer of natural gas in the world. Diversification of supply sources is therefore paramount both for energy security, as well as for competitiveness.

Liquefied natural gas - known as LNG - is natural gas, predominantly methane that has been converted to liquid form at - 162 °C for ease of storage or transport. As a liquid, LNG takes up around 600 times less volume than gas at standard atmospheric pressure. This makes it possible to transport the gas over long distances, without the need of pipelines, typically in specially designed ships or road tankers. When it reaches its final destination it is usually re-gasified and distributed through gas networks – just like gas from pipelines. LNG is also increasingly used as an alternative fuel for ships and lorries.

Importance of LNG for the EU's security of supply

Ensuring that all Member States have access to liquid gas markets is a key objective of the EU's energy union strategy. LNG can give a real boost to the EU's diversity of gas supply and hence greatly improve energy security. Today, the countries in Europe that have access to LNG import terminals and liquid gas markets are far more resilient to possible supply interruptions than those that are dependent on a single gas supplier.

Cargoes of LNG are available from a wide variety of different supplier countries worldwide, and the global LNG market is undergoing a dynamic development with the entrance of new suppliers such as the United States, Russia and Australia.

In 2019, 14 Member States imported a total of 108 billion cubic metres (bcm, gas equivalent) of LNG, 75% more than one year earlier. LNG imports made up 25% of total extra-EU gas imports in 2019. The biggest LNG importers in the EU were Spain (22.4 bcm), France (22.1 bcm), the UK (18 bcm), Italy (13.5 bcm), the Netherlands and Belgium (8.6-8.8 bcm).

Production and imports

Less than 25% of the EU's gas needs are currently met by domestic production. The rest is imported, mainly from Russia (31 %), Norway (28%), and Algeria (5%), beyond LNG sources, as 2019 annual data shows.

In recent years the share of LNG has measurably increased, accounting for around 25% of imports in 2019, with most of that coming from Qatar (28%), followed by Russia (20%), the United States (16%) and Nigeria (12%).

Qatar is currently by far the world's largest supplier of LNG, at around 170 bcm. Other large (>20 bcm) suppliers include Australia,the United States, Nigeria, Malaysia, Russia and Indonesia. Global liquefaction is set to further increase dramatically as new plants in the United States and Australia come on stream over the next few years.

Infrastructures

The EU's overall LNG import capacity is significant – enough to meet around 45% of total current gas demand. However, in the region of south-east of Europe, central-eastern Europe and the Baltic, many countries do not have access to LNG and/or are heavily dependent on a single gas supplier, and would therefore be hardest hit in a supply crisis. It is important to make sure that such countries have access to a regional gas hub with a diverse range of supply sources, including LNG.

Based on the list of EU 'projects of common interest' the LNG strategy includes a list of key infrastructure projects which are essential for ensuring that all EU countries can benefit from LNG.

With any new infrastructure, commercial viability is very important. For a LNG terminal, its utilisation across a whole region, or the choice of lower cost and more flexible technologies, such as floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs), may considerably improve its viability.

In principle, LNG terminals, as with other energy infrastructure, should be financed through end-user tariffs (investment is paid for by all gas consumers as part of their monthly gas bill) or in some cases gas companies bear the costs of construction (the investment is borne by a number of companies in exchange for the right to use the terminal through long-term capacity booking). But even with a sound business case, financing may still be a challenge in some cases.

For projects that are particularly important for security of supply, EU funds, such as the Connecting Europe Facility could potentially help fill the financing gap. EIB loans, and the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), may be another sources of long-term financing.

The EU is the biggest importer of natural gas in the world. Diversification of supply sources is therefore paramount both for energy security, as well as for competitiveness.

Liquefied natural gas - known as LNG - is natural gas, predominantly methane that has been converted to liquid form at - 162 °C for ease of storage or transport. As a liquid, LNG takes up around 600 times less volume than gas at standard atmospheric pressure. This makes it possible to transport the gas over long distances, without the need of pipelines, typically in specially designed ships or road tankers. When it reaches its final destination it is usually re-gasified and distributed through gas networks – just like gas from pipelines. LNG is also increasingly used as an alternative fuel for ships and lorries.

Importance of LNG for the EU's security of supply

Ensuring that all Member States have access to liquid gas markets is a key objective of the EU's energy union strategy. LNG can give a real boost to the EU's diversity of gas supply and hence greatly improve energy security. Today, the countries in Europe that have access to LNG import terminals and liquid gas markets are far more resilient to possible supply interruptions than those that are dependent on a single gas supplier.

Cargoes of LNG are available from a wide variety of different supplier countries worldwide, and the global LNG market is undergoing a dynamic development with the entrance of new suppliers such as the United States, Russia and Australia.

In 2019, 14 Member States imported a total of 108 billion cubic metres (bcm, gas equivalent) of LNG, 75% more than one year earlier. LNG imports made up 25% of total extra-EU gas imports in 2019. The biggest LNG importers in the EU were Spain (22.4 bcm), France (22.1 bcm), the UK (18 bcm), Italy (13.5 bcm), the Netherlands and Belgium (8.6-8.8 bcm).

Production and imports

Less than 25% of the EU's gas needs are currently met by domestic production. The rest is imported, mainly from Russia (31 %), Norway (28%), and Algeria (5%), beyond LNG sources, as 2019 annual data shows.

In recent years the share of LNG has measurably increased, accounting for around 25% of imports in 2019, with most of that coming from Qatar (28%), followed by Russia (20%), the United States (16%) and Nigeria (12%).

Qatar is currently by far the world's largest supplier of LNG, at around 170 bcm. Other large (>20 bcm) suppliers include Australia,the United States, Nigeria, Malaysia, Russia and Indonesia. Global liquefaction is set to further increase dramatically as new plants in the United States and Australia come on stream over the next few years.

Infrastructures

The EU's overall LNG import capacity is significant – enough to meet around 45% of total current gas demand. However, in the region of south-east of Europe, central-eastern Europe and the Baltic, many countries do not have access to LNG and/or are heavily dependent on a single gas supplier, and would therefore be hardest hit in a supply crisis. It is important to make sure that such countries have access to a regional gas hub with a diverse range of supply sources, including LNG.

Based on the list of EU 'projects of common interest' the LNG strategy includes a list of key infrastructure projects which are essential for ensuring that all EU countries can benefit from LNG.

With any new infrastructure, commercial viability is very important. For a LNG terminal, its utilisation across a whole region, or the choice of lower cost and more flexible technologies, such as floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs), may considerably improve its viability.

In principle, LNG terminals, as with other energy infrastructure, should be financed through end-user tariffs (investment is paid for by all gas consumers as part of their monthly gas bill) or in some cases gas companies bear the costs of construction (the investment is borne by a number of companies in exchange for the right to use the terminal through long-term capacity booking). But even with a sound business case, financing may still be a challenge in some cases.

For projects that are particularly important for security of supply, EU funds, such as the Connecting Europe Facility could potentially help fill the financing gap. EIB loans, and the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), may be another sources of long-term financing.

To help prevent potential supply disruptions and respond to them if they happen, EU legislation creates common standards and indicators to measure serious threats and define how much gas EU countries need to be able to supply to households and other vulnerable consumers.

The security of gas supply regulation

|

The security of gas supply rRegulation (EU) 2017/1938 was introduced in 2017, repealing Regulation (EU) 994/2010, which:

To help EU countries design and agree on bilateral solidarity arrangements, the Commission, in accordance with Regulation 2017/1938, has published a non-binding guidance document (Recommendation (EU) 2018/177) on the technical, legal and financial elements that should be included in such arrangements. Each country must appoint a competent authority responsible for the implementation of the regulation. Preventive action plans and emergency plans EU countries must adopt and update a preventive action plan with measures needed to remove or mitigate the gas supply risks identified in their national and common (regional) risk assessments. They must also adopt an emergency plan with measures to remove or mitigate the impact of a gas supply disruption. Previously, the plans had to be updated every two years, but as of 2019 it is every four years.The plans must also be public and include, as of 2019, regional chapters with the cross-border measures agreed by countries to address common risks. The Commission assesses the plans and recommends amendments if necessary. |

EU-wide simulation of disruption scenariosIn

In November 2017, ENTSOG adopted an EU-wide simulation of disruption scenarios, in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2017/1938 on security of gas supply.

Gas Coordination Group

The Gas Coordination Group gives advise to the Commission on the coordination of security of supply measures amongst EU countries, and exchanges information on security of supply with suppliers, consumers and transit countries. The group should also monitor the adequacy and appropriateness of measures to be taken under the Regulation (EU) 2017/1938.

The group meets regularly since 2012 to discuss these matters. The members include national authorities, the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER), the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSOG), the Energy Community and representatives of industry and consumer associations.

In November 2017, ENTSOG adopted an EU-wide simulation of disruption scenarios, in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2017/1938 on security of gas supply.

Gas Coordination Group

The Gas Coordination Group gives advise to the Commission on the coordination of security of supply measures amongst EU countries, and exchanges information on security of supply with suppliers, consumers and transit countries. The group should also monitor the adequacy and appropriateness of measures to be taken under the Regulation (EU) 2017/1938.

The group meets regularly since 2012 to discuss these matters. The members include national authorities, the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER), the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSOG), the Energy Community and representatives of industry and consumer associations.

Diversification of gas supply sources and routes

|

A key part of ensuring secure and affordable supplies of energy to Europeans involves diversifying supply routes. This includes identifying and building new routes that decrease the dependence of EU countries on a single supplier of natural gas and other energy resources. The review of the TEN-E Corridors (Trans-European infrastructure for Energy) has started il 2020 and aims to review strategic planning for energy infrastructure.. TEN-E will continue to connect regions currently isolated from European energy markets, strengthen existing cross-border interconnections and promote cooperation with partner countries. |

Let's see the current EU strategy, which will be updated by the TEN-E revision:

Southern Gas Corridor

Many countries in Central and South East Europe are dependent on a single supplier for most or all of their natural gas. To help these countries diversify their supplies, the Southern Gas Corridor aims to expand infrastructure that can bring gas to the EU from the Caspian Basin, Central Asia, the Middle East, and the Eastern Mediterranean Basin.

Initially, approximately 10 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas will flow along this route when it opens by the end of 2020. Given the potential supplies from the Caspian Region and the East Mediterranean, this amount could potentially be increased by 10-20 bcm of gas per year in the future.

EU actions for expanding the Southern Gas Corridor include:

Mediterranean hub

The creation of a Mediterranean gas hub in the South of Europe will help diversify EU's energy suppliers and routes. To this end, the EU is engaged in an active energy dialogue at political level with North African and Eastern Mediterranean partners.

Taking into account the huge potential of Algeria, both for conventional and unconventional gas resources, as well as the new gas resources in the East Mediterranean and the associated infrastructure development plans, the Mediterranean area can act as a key source and route for supplying gas to the EU.

Israel, Egypt and Cyprus, because of their significant offshore gas reserve, make the Eastern Mediterranean region a strategic partner for the EU in its effort to diversify its gas supply routes. There are several options to bring natural gas from the region to the EU and the world market either by pipeline or as LNG. Notably, there are two Projects of Common Interest (PCIs) in gas involving the Cyprus East Med Pipeline and CyprusGas2EU LNG terminal, where the latter granted significant Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) grants at the end of 2017.

Liquefied natural gas terminals

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) imported to Europe through LNG terminals is a source of diversification that contributes to competition in the gas market and security of supply. To adapt to this evolution of the world gas market, in February 2016, the European Commission presented an EU strategy (COM(2016) 49 final) for LNG and gas storage.

New LNG supplies from North America, Australia, Qatar, and East Africa are increasing the size of the global LNG market, and some of these volumes have already reached the European market.

Considering that most of the existing capacity is located in Western Europe, and that internal bottlenecks exist from the Atlantic coast to the East, the EU strategy has identified a limited number of essential ‘projects of common interest’, mainly interconnectors, that would allow market players from all corners of the EU to benefit from LNG. In addition, as is the case in the Baltics and in South-East Europe, a number of LNG regasification units have been identified as Projects of Common Interest under the Regulation on guidelines for trans-European energy infrastructure ((EU) 347/2013).

Southern Gas Corridor

Many countries in Central and South East Europe are dependent on a single supplier for most or all of their natural gas. To help these countries diversify their supplies, the Southern Gas Corridor aims to expand infrastructure that can bring gas to the EU from the Caspian Basin, Central Asia, the Middle East, and the Eastern Mediterranean Basin.

Initially, approximately 10 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas will flow along this route when it opens by the end of 2020. Given the potential supplies from the Caspian Region and the East Mediterranean, this amount could potentially be increased by 10-20 bcm of gas per year in the future.

EU actions for expanding the Southern Gas Corridor include:

- keeping the infrastructure projects needed for the corridor on the EU's fourth list of Projects of Common Interest (PCI). These are projects which can benefit from streamlined permitting process, receive preferential regulatory treatment, and are eligible to apply for EU funding from the Connecting Europe Facility

- supporting the construction of the Trans Anatolia Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) and the Trans-Adriatic-Pipeline (TAP) to transport gas from Azerbaijan to Italy via Georgia, Turkey, Greece, Albania and the Adriatic Sea by listing them on the PCI lists

- cooperating closely with gas suppliers in the region, such as Azerbaijan

- cooperating closely with transit countries including Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey and Albania

- negotiating with Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan on a potentialTrans-Caspian pipeline to transport gas across the Caspian Sea

Mediterranean hub

The creation of a Mediterranean gas hub in the South of Europe will help diversify EU's energy suppliers and routes. To this end, the EU is engaged in an active energy dialogue at political level with North African and Eastern Mediterranean partners.

Taking into account the huge potential of Algeria, both for conventional and unconventional gas resources, as well as the new gas resources in the East Mediterranean and the associated infrastructure development plans, the Mediterranean area can act as a key source and route for supplying gas to the EU.

Israel, Egypt and Cyprus, because of their significant offshore gas reserve, make the Eastern Mediterranean region a strategic partner for the EU in its effort to diversify its gas supply routes. There are several options to bring natural gas from the region to the EU and the world market either by pipeline or as LNG. Notably, there are two Projects of Common Interest (PCIs) in gas involving the Cyprus East Med Pipeline and CyprusGas2EU LNG terminal, where the latter granted significant Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) grants at the end of 2017.

Liquefied natural gas terminals

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) imported to Europe through LNG terminals is a source of diversification that contributes to competition in the gas market and security of supply. To adapt to this evolution of the world gas market, in February 2016, the European Commission presented an EU strategy (COM(2016) 49 final) for LNG and gas storage.

New LNG supplies from North America, Australia, Qatar, and East Africa are increasing the size of the global LNG market, and some of these volumes have already reached the European market.

Considering that most of the existing capacity is located in Western Europe, and that internal bottlenecks exist from the Atlantic coast to the East, the EU strategy has identified a limited number of essential ‘projects of common interest’, mainly interconnectors, that would allow market players from all corners of the EU to benefit from LNG. In addition, as is the case in the Baltics and in South-East Europe, a number of LNG regasification units have been identified as Projects of Common Interest under the Regulation on guidelines for trans-European energy infrastructure ((EU) 347/2013).

Shale gas and other unconventional hydrocarbons

Unconventional hydrocarbons are resources found in reservoirs with geological characteristics and locations different from those where oil and gas are usually produced. They include

- natural gas from shale formations (shale gas)

- natural gas from coal seams (coalbed methane)

- crude oil from shale formations or other formations with low permeability (tight oil or shale oil)

Extraction and fracking

Unconventional hydrocarbons can contribute to the EU's security of supply and competitiveness. There are however public concerns over their extraction since it is generally more difficult than extracting from conventional sources.

The extraction of shale gas, for instance, requires the drilling of additional wells and is using techniques such as hydraulic fracturing, also called “fracking”. It opens up fissures in the rock by using large quantities of water under high pressure, mixed with sand and other additives in order to release the gas. The EU is working to ensure that such extraction is done with proper environmental and climate safeguards.

EU countries have adopted different policies towards shale gas, ranging from the banning of hydraulic fracturing in France and Bulgaria to explanatory drillings and hydraulic fracturing tests in Poland. Although some countries have previously expressed a strong interest in exploring shale gas resources, the United Kingdom is the only country in Europe where companies pursue such efforts.

Unconventional hydrocarbons can contribute to the EU's security of supply and competitiveness. There are however public concerns over their extraction since it is generally more difficult than extracting from conventional sources.

The extraction of shale gas, for instance, requires the drilling of additional wells and is using techniques such as hydraulic fracturing, also called “fracking”. It opens up fissures in the rock by using large quantities of water under high pressure, mixed with sand and other additives in order to release the gas. The EU is working to ensure that such extraction is done with proper environmental and climate safeguards.

EU countries have adopted different policies towards shale gas, ranging from the banning of hydraulic fracturing in France and Bulgaria to explanatory drillings and hydraulic fracturing tests in Poland. Although some countries have previously expressed a strong interest in exploring shale gas resources, the United Kingdom is the only country in Europe where companies pursue such efforts.

|

What future for shale gas It is not clear whether Europe will resort to this type of fuel andr to other unconventional fuels. The invasiveness of the extraction techniques and the resistance of the population lead us to believe that these fuels could be used as an extreme solution. The European Commission has already carried out geological studies, prospecting and surveys on the potential of unconventional oil and gas resources, even as far as Ukraine, with the EUOGA (European Unconventional Oil and Gas Assessment) project, carried out from September 2015 to March 2017. A key result from the EUOGA project shows that shale gas resource estimates amount to 89 trillion cubic meters. The corresponding estimate for shale oil is set at 31 billion barrels. The researchers used a so-called P50 estimate to determine these estimates. P50 is a median value that indicates at least a 50% probability that existing resources are equal to or greater than the best estimate. The Joint Research Center (JRC) released a comprehensive report on shale gas and shale oil resource assessment in February 2017 as part of the project. |

|

Environment and climate concerns The European Commission is committed to the environmental integrity of unconventional hydrocarbons, and has undertaken a series of measures to ensure that extraction is done in a safe, responsible and environmentally friendly way. In January 2014, the Commission issued recommendations for EU countries when creating or adapting legislation related to hydraulic fracturing. The recommendations were accompanied by a communication outlining opportunities and challenges stemming from shale gas extraction in Europe and an impact assessment on the socio-economic and environmental impacts. To further address concerns, the European science and technology network on unconventional hydrocarbons was established in 2014 to collect, analyse and review results from shale gas exploration projects in the EU, including the development of technologies used in unconventional oil and gas projects. The network concluded its work in 2016. |

2021: The EU's war on fossil gases

|

On 15 December 2021, the Commission has adopted a set of legislative proposals to decarbonise the EU gas market by facilitating the uptake of renewable and low carbon gases, including hydrogen, and to ensure energy security for all citizens in Europe. The Commission is also following up on the EU Methane Strategy and its international commitments with proposals to reduce methane emissions in the energy sector in Europe and in our global supply chain. The EU want to decarbonise the energy it consumes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 and become climate-neutral by 2050. The Commission has presented two proposals:

The aim is to create the conditions for the transition from fossil natural gas to renewable and low-carbon gases, in particular biomethane and hydrogen, and, at the same time, to strengthen the resilience of gas supply in Europe. The solution devised by the Commission The solution is to prepare a market for hydrogen in Europe, creating the right environment for investments and allowing the development of dedicated infrastructures, including for trade with third countries. The market rules will be applied in two phases, before and after 2030, and concern in particular access to hydrogen infrastructure, the separation of hydrogen production and transport activities and the determination of tariffs. A new governance structure in the form of the European Network of Network Operators for Hydrogen (ENNOH) will be created to promote a dedicated hydrogen infrastructure, cross-border coordination and construction of interconnection networks and develop specific technical rules. The proposal foresees that the national network development plans should be based on a joint scenario for electricity, gas and hydrogen. It should be aligned with National Energy and Climate Plans, as well as EU-wide Ten Year Network Development Plan. Gas network operators have to include information on infrastructure that can be decommissioned or repurposed, and there will be separate hydrogen network development reporting to ensure that the construction of the hydrogen system is based on a realistic demand projection. The new rules will make it easier for renewable and low-carbon gases to access the existing gas grid, by removing tariffs for cross-border interconnections and lowering tariffs at injection points. They also create a certification system for low-carbon gases, to complete the work started in the Renewable Energy Directive with the certification of renewable gases. |

|

This will ensure a level playing field in assessing the full greenhouse gas emissions footprint of different gases and allow Member States to effectively compare and consider them in their energy mix. In order to avoid locking Europe in with fossil natural gas and to make more space for clean gases in the European gas market, the Commission proposes that long-term contracts for unabated fossil natural gas should not be extended beyond 2049.

Another priority of the package is consumer empowerment and protection. Mirroring the provisions already applicable in the electricity market, consumers may switch suppliers more easily, use effective price comparison tools, get accurate, fair and transparent billing information, and have better access to data and new smart technology. Consumers should be able to choose renewable and low carbon gases over fossil fuels. High energy prices for gas in 2021 and 2022. EU propose a "toolbox" High energy prices in last months have drawn attention to the importance of energy security, especially in times when global markets are volatile. For this reason, the Commission proposes to improve the resilience of the gas system and strengthen the existing security of supply provisions, by emergency income support to households, state aid for companies and targeted tax reductions. as promised in the Communication and Toolbox on Energy Prices of 13 October, and as requested by Member States. |

In case of shortages, no household in Europe will be left alone, with enhanced automatic solidarity across borders through new pre-defined arrangements and clarifications on controls and compensations within the internal energy market.

The proposal extends current rules to renewables and low carbon gases and introduces new provisions to cover emerging cybersecurity risks. Finally, it will foster a more strategic approach to gas storage, integrating storage considerations into risk assessment at regional level. The proposal also enables voluntary joint procurement by Member States to have strategic stocks, in line with the EU competition rules. Go to Energy Price here.

Tackling Methane Emissions

In parallel, in a first-ever EU legislative proposal on methane emissions reduction in the energy sector, the Commission will require the oil, gas and coal sectors to measure, report and verify methane emissions, and proposes strict rules to detect and repair methane leaks and to limit venting and flaring. It also puts forward global monitoring tools ensuring transparency of methane emissions from imports of oil, gas and coal into the EU, which will allow the Commission to consider further actions in the future.

The proposal would establish a new EU legal framework to ensure the highest standard of measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) of methane emissions. The new rules would require companies to measure and quantify their asset-level methane emissions at source and carry out comprehensive surveys to detect and repair methane leaksin their operations. In addition, the proposal bans venting and flaring practices, which release methane into the atmosphere, except in narrowly defined circumstances. Member States should also establish mitigation plans, taking into consideration methane mitigation and measurement of abandoned mine methane and inactive wells.

Finally, with respect to the methane emissions of the EU's energy imports, the Commission proposes a two-step approach. First, importers of fossil fuels will be required to submit information about how their suppliers perform measurement, reporting and verification of their emissions and how they mitigate those emissions. The Commission will establish two transparency tools that will show the performance and reduction efforts of countries and energy companies across the globe in curbing their methane emissions: a transparency database, where the data reported by importers and EU operators will be made available to the public; and a global monitoring tool to show methane emitting hot-spots inside and outside the EU, harnessing our world leadership in environmental monitoring via satellites.

As a second step, to effectively tackle emissions of imported fossil fuels along the supply chain to Europe, the Commission will engage in a diplomatic dialogue with our international partners and review the methane regulation by 2025 with a view to introducing more stringent measures on fossil fuels imports once all data is available.

Background

Today's proposals, together with the legislative packagepresented on 14 July 2021 and the revision of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive unveiled today, represent an important step in Europe's decarbonisation path and will help to deliver the target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, and becoming climate neutral by 2050.

The legislative proposals adopted today follow from the strategic vision set out in the EU energy system integration strategy, EU Hydrogen Strategy and the EU Methane Strategyin 2020. The EU is leading international action to tackle methane emissions. At the COP26 UN Climate Conference, we launched the Global Methane Pledge in partnership with the United States, whereby over 100 countries committed to reduce their methane emissions by 30% by 2030 compared to 2020 levels.

The proposal extends current rules to renewables and low carbon gases and introduces new provisions to cover emerging cybersecurity risks. Finally, it will foster a more strategic approach to gas storage, integrating storage considerations into risk assessment at regional level. The proposal also enables voluntary joint procurement by Member States to have strategic stocks, in line with the EU competition rules. Go to Energy Price here.

Tackling Methane Emissions

In parallel, in a first-ever EU legislative proposal on methane emissions reduction in the energy sector, the Commission will require the oil, gas and coal sectors to measure, report and verify methane emissions, and proposes strict rules to detect and repair methane leaks and to limit venting and flaring. It also puts forward global monitoring tools ensuring transparency of methane emissions from imports of oil, gas and coal into the EU, which will allow the Commission to consider further actions in the future.

The proposal would establish a new EU legal framework to ensure the highest standard of measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) of methane emissions. The new rules would require companies to measure and quantify their asset-level methane emissions at source and carry out comprehensive surveys to detect and repair methane leaksin their operations. In addition, the proposal bans venting and flaring practices, which release methane into the atmosphere, except in narrowly defined circumstances. Member States should also establish mitigation plans, taking into consideration methane mitigation and measurement of abandoned mine methane and inactive wells.

Finally, with respect to the methane emissions of the EU's energy imports, the Commission proposes a two-step approach. First, importers of fossil fuels will be required to submit information about how their suppliers perform measurement, reporting and verification of their emissions and how they mitigate those emissions. The Commission will establish two transparency tools that will show the performance and reduction efforts of countries and energy companies across the globe in curbing their methane emissions: a transparency database, where the data reported by importers and EU operators will be made available to the public; and a global monitoring tool to show methane emitting hot-spots inside and outside the EU, harnessing our world leadership in environmental monitoring via satellites.

As a second step, to effectively tackle emissions of imported fossil fuels along the supply chain to Europe, the Commission will engage in a diplomatic dialogue with our international partners and review the methane regulation by 2025 with a view to introducing more stringent measures on fossil fuels imports once all data is available.

Background

Today's proposals, together with the legislative packagepresented on 14 July 2021 and the revision of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive unveiled today, represent an important step in Europe's decarbonisation path and will help to deliver the target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, and becoming climate neutral by 2050.

The legislative proposals adopted today follow from the strategic vision set out in the EU energy system integration strategy, EU Hydrogen Strategy and the EU Methane Strategyin 2020. The EU is leading international action to tackle methane emissions. At the COP26 UN Climate Conference, we launched the Global Methane Pledge in partnership with the United States, whereby over 100 countries committed to reduce their methane emissions by 30% by 2030 compared to 2020 levels.

TIP: Refer to the Hydrogen page for this gas.